Writing for Games, Part Two: The experts' advice

Leading writers share insights and advice on preparing for a career in crafting narratives for video games

Yesterday, we published the first part of this two-part special on writing for games, in which five successful writers talked us through a brief history of storytelling in video games.

Today, we continue the discussion by finding out some of the lessons they've learned during their careers – starting with the need to understand collaborative games writing is even more collaborative than other forms.

Writers are team players

Writing is generally viewed as a solitary profession, but most professional writers benefit from collaboration. Journalists seek out good editors. Novelists want to work with the best agents and publishers, who will try to find ways to improve draft work. Movies and TV shows are often created by teams, who are obliged to work with a host of stakeholders including executives and actors. These relationships can be prickly or downright dysfunctional.

In gaming, the terms of collaboration are much, much wider and deeper than even the most complex movie. Movies start with a script, and although that script is likely to be altered significantly during production it is (or ought to be) the project's keystone.

But in a game, the script is generally less important than the player's interaction. The gameplay comes first. Play mechanics are iterative and experimental. A game changes in many more ways during production than a movie. This means that the writers are constantly creating work that ends up being unused, or they are repeatedly rewriting scenes as the design changes.

Expensive and high-profile voice-actors are now common in games, and coming from mature art forms like movies, they have little patience for under-par dialogue. Their oversized importance in a game's production affords them more say in their character's development, which the writers must accommodate. This is not always a bad thing. Many actors come with a trove of experience which can be useful to writing teams.

The upshot is that, apart from an ability to tell stories well, the best attributes for game writers are flexibility and chill and an ability to leave ego out in the parking lot. (These personality traits are not commonly associated with writers.)

Jedidjah Julia Noomen, who has written for TV, theatre and dozens of games such as the upcoming A Plague Tale: Requiem, says: "If you are the kind of person who mainly enjoys working on your own, you are going to have a hard time working in games."

No Man's Sky and Metro Exodus writer Greg Buchanan adds: "Writers who come into games from other fields often struggle to appreciate that they're now part of a much larger team. [Now] they're working with people for whom narrative is a concern, but it's not always a primary concern. It's essential to be flexible and open to frequent changes in project direction."

He adds: "For younger writers coming in, I would say that a key skill to learn quickly is basic office behavior. Knowing how to communicate and interact with co-workers is a discipline in its own right, and if you're in a writing team, or writing alongside other stakeholders, you've got to know how to deal with people, and with the inevitable conflicts. It's not at all like writing a novel, in which most of the work is done alone, and interacting with editors and agents often comes only at the end.

"It's also important to recognize how the specific game company you’re working with operates, because they're all different. Can you recognize the ideas that are set in stone, as opposed to those that are open for debate? Often the tiniest details are actually incredibly important to game directors or company leaders."

Tanya X Short, founder and creative director of Boyfriend Dungeon developer Kitfox Games, observes that two of the most valuable assets – even for the best writers – are flexibility and "solution-oriented humility."

"If you are the kind of person who mainly enjoys working on your own, you are going to have a hard time working in games"

Jedidjah Julia Noomen

"We all have to realize that rewriting a piece of dialogue will always be cheaper than redoing the art or remaking a feature," she says. "That doesn't mean that you are less valuable or that your work is less valuable. But it does mean that in the iterative process of making video games you are the most likely to do the rework. That's the reality of being a writer in games."

Writers who work in teams are often exhorted to pick their battles carefully. But it's often the case that writers do not wield enough power to push back against awful ideas that have come down from on high.

"The power anyone has to push back against potentially harmful decisions made by upper management is directly related to their ability to individually withstand late-stage capitalism," says Xalavier Nelson Jr, writer and creator of An Airport for Aliens Currently Run by Dogs and Witch Strandings.

"People need to pay their rent. And so there are thousands of invisible decisions that harm the production, or dropped ideas that might have made it so much better, that are placed at the door of the writers but were never really in their hands."

Writing for player interactivity

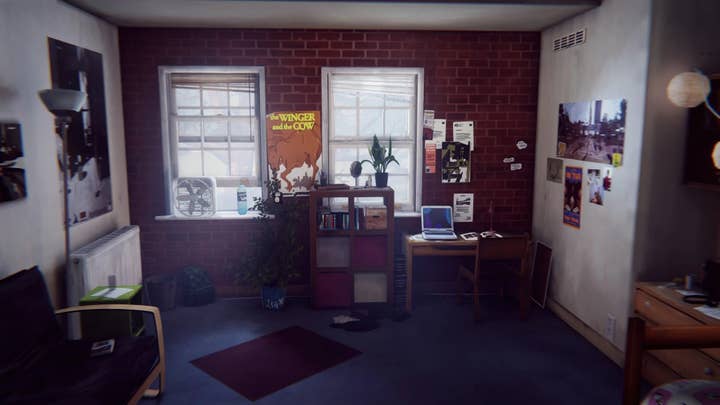

Much of the collaborative intimacy associated with game development is driven by the fundamental nature of video games, which is audience participation. In theatre, the curtain raises and the audience sees how the stage is dressed. If we see a student's dorm room with an accompanying twang of '50s pop music, we can be pretty sure of the story's setting, and perhaps its nature. Great care is taken to get these details right, for the sake of historical accuracy, but more importantly, to set a narrative tone.

In a game, the same is true. But the player is also going to be poking around in that dorm room. They may be required to speak to some of the people in the room, or to dig through their belongings, or set up a trap. They may leave the room to explore other areas. Up to a certain point, the game's success depends on the player having as much freedom to move around and do stuff as possible.

For game writers, this multiplies their workload, or to be more accurate, it tests their powers of imagination and storytelling. The game must move in a forward direction, just like a theatre play, but in the meantime, the player is at the center of the action, and they must be given interesting things to do, not just interesting things to see and hear.

"As a game writer we have to keep so many more things in mind when we're planning out the beats and the pacing and the character movements." says Short. "Everything about the audience experience is so much more multifaceted than linear, passive media."

Noomen adds: "You can definitely make a traditional theatre play without thinking too much about the audience. You can tell the story you want to tell, and your concern is basically 'Will they get what I'm trying to say?' But when you're writing for a game, you're always thinking about your players first, and that is a big difference. Even with simple interactive fiction games, where you're just pressing a button to progress the story one way or another, it's still interaction. Anticipating your audience will always be part of what you're doing."

Action games are especially challenging for writers. Much of the dialogue comes down to mission instructions, while attempts to create sympathy between the player and the protagonist is limited by an experience dominated by extreme and unrelenting violence.

"There's an old saying in TV and movie writing, that action equals character," says Rhianna Pratchett, whose many writing credits include Heavenly Sword, Lost Words: Beyond the Page and the rebooted Tomb Raider trilogy. "You've got to pay attention to what you're having characters do, because that's telling you who they are.

"But in games, action is a completely different design department and they don't necessarily care about what you want to do with the characters. They've got their own goals. They want to make a fun experience for the player."

Short adds: "I think it's generally known that among game developers, that we are tired of writing for serial killers. It's a standard fantasy that you can be the good guy and chill out and kill some bad guys. But as a writer, it's not an interesting exercise."

Narrative rejection

Even the most brainless shooting game comes with a story, but game developers and publishers are acutely aware that many players don't care about narrative or character or plot. And some are actively hostile to anything that gets in the way of action. It's a perfectly reasonable perspective for someone who just wants to shoot a bunch of enemies.

"A lot of players are happy with [basic instructions] to be the extent of the dialogue," says Buchanan. "They don't necessarily care about anything arguably deeper, like character development or even the larger plot.

"That makes games weird. Some players are actually resistant to overt signs of narrative. Nobody buys a book who isn't interested in the story, but plenty of people play games that way, wanting to be entertained on their own terms. As a result, sometimes, it's better to optimize the functional aspects of dialogue relating to gameplay directions, and then tease and invite people into any deeper narrative, rather than just going full hog with it."

The future of writing for games

The vast improvement in game narrative, and the increase in the numbers of writers and narrative designers being hired, does not mean that more progress is unnecessary. Generally, writers are paid less than other professionals in game development teams.

"There is a common adage that words are cheap," says Nelson Jr. "And to a degree that is true. But the thing I have personally witnessed is that when you have a writing professional in the room, their perspectives can lead to pivots that tie the overall game experience together. That can end up being worth literally millions of dollars.

"We are tired of writing for serial killers. Be the good guy, chill out and kill some bad guys - as a writer, it's not an interesting exercise"

Tanya X Short, Kitfox Games

"But the number of visible games writers is quite low, considering the impact that they have individually on games. Not only is that a sad thing, it also becomes dangerous for them when the studio shuts down, or they lose work, or the game gets bad reviews. The writers are often the skilled professionals who were trying to save it every step of the way. Now having that on their resume, just trying to justify their careers continuing is difficult. They're not like programmers who can go to work for a social media or enterprise software company – and they get paid significantly less than those programmers."

Another common mistake game developers and publishers make is to bring in writers near the end of a project, to layer some kind of plausible narrative onto the action.

"Getting writers involved early on is essential," says Pratchett. "A lot of what writers do is invisible. They're building the body of the story. It's not a good idea for a game director to hire writers late into the project, and then say 'Okay, write me an amazing story."

A big challenge facing game writing is that it's a skill that remains largely ignored at the educational level. Noomen says: "One of the big complaints that I hear from people studying game development is that there is not a lot of writing or narrative design being taught.

"Students studying game design should have a basic knowledge of those things, even if they're not writers. Narrative design is so important – just thinking about how the story fits with the game design will give them a better understanding of game design as a whole.

"So there's a disconnect at the teaching level. If we start teaching juniors more about what game writing actually is, then they will have more value as potential developers in the job market."

I asked all of the writers I spoke to, what advice they would give to young writers looking to break into games. They all replied that understanding how games are made is absolutely key.

For example, writers who are interested in telling their own stories are often dissuaded by their lack of skills in other departments of game development. The good news is that game-making tools are becoming more user-friendly.

"For decades, writers have been terrified of things like programming," says Short. "But these days there's less programming than you might think, and what there is, isn't that hard to learn. Our culture perceives programming as this weird wizardry that only geniuses can do, but it's really not. There are so many tools out there."

Nelson Jr. sums up the general advice to newbies: "Learn the vocabulary of other disciplines as extensively as you can. As a games writer, you will have more success bringing your words to life if you understand the costs and the mechanics of game development as a whole.

"The number one thing I have found useful, regardless of the size of the team I've worked with, regardless of budget, has been the more I know the language and perspective, and vocabulary of the other disciplines that will be involved in bringing a game experience to life, the better I work, and the better I'm able to solve problems. I've worked on around 70 games now, and I'll say that being interested in the craft of game development as a whole, being able to speak the language and to know the considerations of other disciplines, has been invaluable."

More GamesIndustry.biz Academy guides to writing for games