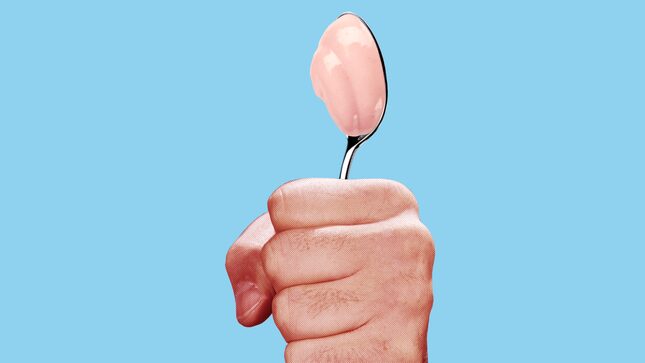

The Rise and Fall of 'Bro-gurt,' the Macho, Ab-Obsessed Snack for MEN

In Depth

Graphic: Elena Scotti (Photos: Getty Images, Shutterstock)

In 2013, a blonde-haired woman in a “sexy nurse” costume (low neckline, high hemline) worked a booth at the Food Expo of Natural Products, pitching a new option: Powerful Yogurt. She offered passers-by ultrasounds of their stomachs so they could “find their inner abs,” the brand’s tagline. The packaging further proclaimed the brand’s masculinity, jet-black packaging with a bull’s horns emblazoned on the front of every cup; every 8-ounce container had bumpy little ridges of six-pack abs on the sides. This was yogurt for MEN. Grub Street quickly christened it “bro-gurt.”

Before bro-gurt, if you wandered in the dairy section at the grocery store, pastoral rows of individual yogurt cups stretched before you. Their packaging was often white, perhaps splotched with the colors of the fruits in their flavors, like pink-ish strawberry, pale blueberry, or pastel peach. Their labels boasted low- or nonfat status and preached about probiotics. But then protein became the king of food trends, symbolizing wellness in all its messy aspirational glory. Riding this wave of amino acid enthusiasm, bro-gurt tried to renegotiate yogurt’s perceived gendered meaning—it’s for MEN!—and nutritional prominence—it’s SCIENCE!—only to be subsumed, ultimately, by the wider enthusiasm for Greek yogurt amongst wellness trends.

Yogurt wasn’t always the dairy darling it is in the U.S. today. Before the 1960s, very few Americans knew of yogurt, let alone ate it—so few that in 1962 Dannon ran ads urging consumers to question their yogurt hesitancy. Conversely, yogurt has a longstanding place in food cultures throughout Europe, the Mediterranean, South Asia, Russia, and the Middle East, where eaters of all ages and genders consume it, often unsweetened and plain, or in sauces and other dishes. In the United States, the “hippies” of the counterculture were fringe yogurt consumers, making it at home in the 1960s and 1970s, along with foods like bean sprouts and brown rice. (The Smithsonian National Museum of American History even includes a home yogurt maker and an earthenware yogurt crock in their food history exhibit.) By the 1980s, commercial yogurt brands, like Dannon, finally made mainstream inroads into American supermarkets, and yogurt slowly became part of many eaters’ daily diets.

As yogurt began a gradual journey to American cultural acceptance, it retained its health halo. Amongst growing public health concerns in the 1980s about dietary fat, cholesterol, and increasing body weights, the food industry positioned low- and nonfat yogurt as a nutritious food that offered calcium, potassium, and “active cultures” to boot. In 1992, when the yogurt market was valued at $1.135 billion, yogurt even earned coveted recommended servings in the Food Guide Pyramid. Sparked, at least in part, by its glowing nutritional properties, yogurt’s eventual popularity was a food industry dream. By 2014, Americans drank 42 percent less milk than they did in 1970, but ate 1700 percent more yogurt.

As brands like Dannon and Yoplait marketed sugary yogurt options to children in the 1980s and 1990s, they also marketed yogurt aggressively to women, in effect gendering yogurt as a “feminine” food in the American market. These yogurts often included “light” in the name, offering featherlight fare with the promise of a lower weight. Ad campaigns positioned these yogurts not as healthy snacks, but as “virtuous” aspartame-filled desserts women could consume while on low-calorie diets. In one ad, a woman peers into a refrigerator, eyeing a raspberry cheesecake. We hear her inner monologue as she ponders, “I could have a medium slice and some celery sticks, and they’d cancel each other out, right?” As she performs this caloric calculus, a slim female co-worker bounces into frame and grabs a raspberry cheesecake yogurt from the adjacent shelf. We are to believe that she has it all: her cake (well, yogurt), and she eats it too. But it’s not cake, not really. Like other yogurts of this ilk, Yoplait came in multiple cheesecake flavors—amaretto, raspberry, and strawberry— as well as caramel apple, cookies ‘n cream, and pie flavors, like Boston Creme or key lime. Although ads sometimes depicted a husband or boyfriend stealing a dessert-flavored yogurt for themselves, the diet culture sales pitch targeted women differently, given social demands for thinness.

With Activia, launched in the U.S. in 2006, Dannon made a different sort of slenderizing promise: that it could help regulate your digestive system in just two weeks, reducing discomfort and bloat, and its supposed appearance of fatness. Activia ads sometimes didn’t even depict full women’s bodies, just a bare, light-skinned, flat stomach. Amy Vidali describes these toned tummies as “gastrointestinal pornography,” as these ads objectified women’s bodies and eroticized healthy eating.

This was the context for the advent of Powerful Yogurt; when the brand arrived, proclaiming itself the “first yogurt for men,” their CEO wasn’t wrong to point out that the yogurt shelf was “light blue, light pink, white…everyone is talking to women and their digestive health.” Powerful Yogurt wasn’t the only one busting in either. In 2013, high-protein frozen yogurt ProYo also launched in black packaging, as did Dannon’s Oikos Triple Zero in 2015. But Powerful Yogurt was a relative standout; the most brutishly bro-gurt-y of them all. The brand didn’t just infiltrate the yogurt shelf with hues dark as midnight. It launched a marketing storm of misogyny.In addition to the aforementioned sexy nurse promotion, a product launch commercial starred a man using his six-pack abs to magically jumpstart a truck and light a match. In others, a man used his abs to make a woman in short shorts dance and cause the button on a woman’s shirt to pop off, exposing her. Print ads decreed “in the battle for women abs always win,” defeating competitors like cute babies and puppies. The brand launched a microsite where men could scroll the page to view eroticized images of women only by doing crunches.

The attention quickly rolled in. But journalists and talk show hosts covered Powerful Yogurt’s launch in much the same way they recently ceded bemused promotional space to KFC’s sexy Colonel Sanders mini-movie. That nuance seemed lost on the folks at Powerful Foods (renamed from Powerful Men), as they celebrated their “earned media coverage.” But within months of their launch, Powerful Yogurt scrapped their misogynistic man-focused marketing, not because it was offensive and gross (though it was) but because the product itself proved popular with women too. Greek yogurt, specifically, fueled the rise of “men’s” yogurt. Rather than marketing yogurt’s relatively low calories, reduced fat, or sweetened flavors—all of which had been historically broadcasted to women—Greek yogurt (at least in the U.S.) proclaimed its higher protein content, generally perceived as a “masculine” macronutrient. But this gendered subtext resonated with far more than just men. Greek yogurt was having its moment, with everyone. It capitalized upon American eaters’ growing “wellness” obsession with protein, which still shapes the food industry, from the dairy case to food for babies and even pets.

All the bro-gurts benefited from the protein-centric Greek yogurt boom—and boom it did. In 2007, Greek yogurt made up just 1 percent of refrigerated yogurt sales, but skyrocketed to 44 percent in 2013 and nearly 50 percent by 2015. Hitting shelves in 2007, Chobani was one of the first Greek yogurt brands to break through in the U.S., and Americans finally realized the deliciousness of Fage, which began in Athens, Greece in 1926. Existing brands, like Dannon’s Activia, also launched Greek varieties. Yoplait even tried to go after men with a Greek option and the ad campaign, “A Man of Yogurt,” featuring well-muscled actor Dominic Purcell. Notably, though, yogurt for men was almost always pitched as a protein-packed snack rather than a pathetic dessert substitute.Within this Greek yogurt explosion, then, what defined bro-gurt? Well, it wasn’t just a high-protein yogurt. There were plenty of those, marketed to both women and men. Bro-gurt was about gender anxiety. Bro-gurt animated fears that because yogurt in the United States had been perceived as feminine and mostly marketed to women (and children), yogurt somehow wasn’t manly. Bro-gurt had to “man up” with black packaging and exaggeratedly masculine (or even misogynistic) advertising. None of which is, or has to be, true. And yet, bro-gurts were a thing, for a hot (frustrating) minute.

That moment passed, though. Like Powerful Yogurt, most bro-gurts softened their focus on men after launching. ProYo dropped its black packaging and rebranded as Swell, before it went out of business. Oikos Triple Zero still comes in a black cup, but with brightly colored lids; ads have starred female athletes, while another starred NFL players’ glutes. Within this shifting market, Powerful Yogurt announced its retirement in November 2020. In an email with the cringeworthy subject line, “Bro-gurt Out!”, Powerful Foods announced they were “saying goodbye to our first ever Powerful product. Our bro-gurt, the one that disrupted all dairy shelves, the first with black packaging in the category.” The fact that the company willingly referred to their product as bro-gurt, as a deranged badge of honor, demonstrates how little they fathom, let alone acknowledge, their role in gendering food in negative and disparaging ways. Putting yogurt in a larger black cup, adorning it with masculine symbols, and marketing it with blatantly sexist messaging is not disruption. It’s misogyny, and none of us needs that in our yogurt.

In more recent years, U.S. consumption of Greek yogurt is slowing, growing flat, or even slightly decreasing. And Americans still consume less yogurt overall than Europeans. Loosely tethered to American food culture, yogurt has both suffered and benefited from relatively fickle consumer whims. Recently, U.S. yogurt purchasing has shifted to Icelandic yogurt (skyr) and non-dairy varieties, while Keto devotees are buying higher-fat options. Over the past forty years, marketing strategies have variably promoted yogurt for women, for children, and for MEN. Today’s dairy case is more diverse in a number of ways: different ingredients, nutritional profiles, flavors, package shapes and colors, lifestyle messages, and intended consumers. Purposefully more ambiguous, the gendering of yogurt in the U.S. is now more inclusive; there are, at the least, no more three-dimensional abs jutting out on the dairy aisle.

Emily Contois, PhD is Assistant Professor of Media Studies at The University of Tulsa. She is the author of Diners, Dudes, and Diets: How Gender and Power Collide in Food Media and Culture and the co-editor of a book on food Instagram.