There is a very good chance you’ve played a PopCap game. More extraordinary, there’s a very good chance everyone you know, including your parents, have played a PopCap game. For about 10 years, there was one name in casual gaming, and that name was almost Sexy Action Cool.

Whether it was Peggle, Bejeweled, Bookworm or Plants Vs Zombies, whether played on mobile, PC, Facebook, console, inside World of Warcraft, or on a Palm Pilot, there was a time around 2009 where PopCap’s games were ubiquitous, when everyone and their mother would have tried PopCap’s products. So how did this happen? How did one studio manage to occupy every corner of gaming, from dial-up downloads to cellphones, from casual gaming portals to Valve’s Orange Box? And how did it go from a three-person indie project to a $650m+ sale to EA?

It began with a game called ARC. In 1995, Brian Fiete and John Vechey were two college students who were fascinated by the earliest iterations of multiplayer gaming. They put together a 2D capture-the-flag concept that Vechey believes was one of the first downloadable multiplayer games. Back then connecting players was tricky, so they approached Total Entertainment Network (TEN), a company that specialised in adding multiplayer modes to popular games. There they met Jason Kapalka, a former games journalist and one of the original members of TEN, who was put to work on ARC. Or as Kapalka recalls, “They were definitely two 19-year-old kids out of an Indiana trailer park. I was given the job of trying to entertain them.”

Vechey and Fiete eventually got jobs at Sierra Online, but, as Kapalka puts it, all three felt “a little disgruntled with our work environment.” They decided to start their own company. Kapalka had already created a company called Sexy Action Cool, a name inspired by a promotional poster for Robert Rodriguez’s movie, Desperado. At one point he and Vechey had used it to release a since-abandoned strip poker game, Foxy Poker, and the company was lying dormant. So to save time, they used that. “In retrospect, probably not the best title,” acknowledges Kapalka, but “the URL was certainly available.” (I strongly recommend against checking it today.)

The trio’s aim was to create simple, downloadable games, that they would be able to license back to companies like Microsoft and Pogo (formerly TEN). They believed they could do it far more efficiently than these big studios, and hopefully make enough money to keep themselves ticking over. So, giving it a go, the first thing they tried their hands at was a little match-3 game called Bejeweled.

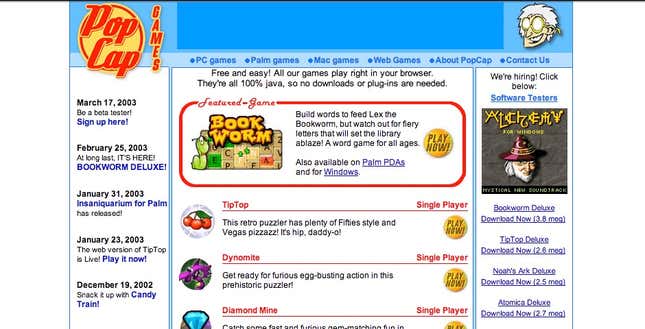

In 2000, Jason Kapalka was based in the Haight, San Francisco, while John Vechey and Brian Fiete were in Renton, Washington, each working out of their own apartments. It was split up like this that they first started putting together what would eventually become Bejeweled. Originally conceived under the name “Diamond Mine”, it was a simple game in which you ‘mined’ gems by swapping tiles to make lines of three or more. And while it wasn’t the first match-3 game, it was certainly the first most people played. “The original was, I think, a game called Shariki,” remembers Kapalka. “A Russian game. But to be honest we weren’t aware of that. What we were aware of was someone had found a really crappy Javascript game. It was called Colors Game, this really primitive game, it didn’t have sound effects, animation, didn’t even really have graphics. It was just a bunch of colored squares that you could swap, and if you made a row of three they disappeared and it fell down. We thought: this is an interesting mechanic, we can probably make a better game with this idea. Brian went off and programmed a better version of the game in Javascript.”

John Vechey picks up the story. “Brian had programmed a different version of it in 24 hours, and then 24 hours later Jason had done some art added on top. I swear, it was like four days later I showed my uncle and he said, ‘Hey, this is fun to play.’ Then we had three months of trying to make it into more of a game, polishing it, and then we had the insecurity of people saying, ‘I played it for five hours, but it’s not really a game.’ You fucking played it for five hours! What the hell!”

“I think Bejeweled might have been the first new, actual good game in that space,” says Brian Fiete. “It was wide-open easy,” he says of an era before quality seemed a priority to others developing online games. “This was before Flash was good, so there were a lot of really, really terrible Flash games. No one took it seriously. Pogo was probably the best of the bunch, but it was gambling games, poker, simple slots, but they weren’t actually good. They were made to be timewasters with a chatroom attached, where they would cycle ads at the top. Microsoft had a portal that had some really, really, really bad games. No one who was working in the space cared about games, they just threw out as much crap as they could.”

PopCap’s earliest mission, and one that remained at least until the late 2000s, was to take the mainstream market as seriously as developers as they took the specialist market as gamers. As Fiete puts it, “It was a revelation to a lot of people that it was possible to make a small online game that played well.”

In those early months of 2001, it turns out their carving of the casual gaming market was something of a happy accident. As they tested Bejeweled, they had a timed and untimed mode. They’d assumed timed would be the default. Untimed, as Kapalka puts it, “There was not much you could do. You played until the luck of the draw meant there were no more matches.” And yet they discovered this was the version everyone wanted to play. Initially confused, they eventually labelled this “The Games For Mom idea.” “My mom doesn’t know about balance or fairness or that stuff, but she just likes playing the version with no timer,” Kapalka said. “That was the beginning of the casual game idea. About not having to cater to the hardcore gamer demands. There’s still a lot of people out there who enjoy playing games, but they want to do it their own way.”

Sexy Action Cool certainly didn’t really feel like the right name for this. Plus there had been some issues with visas at the border, questions about the name appearing on invoices, and they realized that if they wanted to capture this family-friendly space, it had to change. So why PopCap? Because Kapalka wanted the word “Pop” in there, he said, and it was the first short URL they could find that was free. Had another URL been available, we’d be reminiscing about PopFrog today.

The three initially offered to sell Bejeweled to gaming portals run by Microsoft and Pogo, for $50,000. Had either said yes, that’d be the end of this story. Instead, they both declined and offered to rent the games for $1,500 a month, a decision that meant PopCap still owned the game and would eventually be able to earn unfathomable amounts of money from just that one title.

Everyone I spoke to acknowledged the incredible freedom to spend so much time, and put so much care into their casual games, was only possible because of the consistent revenue that came in from Bejeweled’s phenomenal success. Taking advantage of the burgeoning home internet of the early 2000s, they created a model where people could play a simpler version of Bejeweled for free online, or download the “Deluxe” edition which came with limited free play before it would ask for credit card details and 20 of your dollars. That premium deal was far cheaper for players than paying the per-minute AOL fees to be online, and it meant the phone line was clear. “In retrospect,” says Kapalka, “it was the second coming of shareware.” This method of selling their games was so alien at the time that companies like Microsoft refused to even try it. Despite coinciding with the dot-com bubble burst, publishers still believed the money was in the advertising. And they weren’t the only ones who didn’t believe it would work.

Jason Kapalka told me a story about how at this point John Vechey’s mother had expressed concerns at his quitting a “proper job” to do this “video games thing”, and told him, “You’ll not make any money just sitting around on the couch!” Vechey laughs, surprised at just how wrong Kapalka had remembered the story. “My mom didn’t say this! A character from the movie Clerks said this!” He picks up the rest of the tale. “In the early days of PopCap, Brian had made this program that would go ‘KERCHING!’ whenever we had sold a game. Me and some friends were watching Clerks, and there’s a line in it where someone says, “You can’t just sit around on a couch making money.” And for some reason my speakers were turned up really high, and that thing went, ‘KERCHING!’ at that exact moment. It couldn’t have been funnier, because we were just sitting on the couch making money.”

Eventually, Kapalka says, they had to turn off the cash register sound because they were coming too frequently and it was getting annoying.

Before everyone was in the same Seattle office, with Kapalka now living in Vancouver, Fiete built a a tool for everyone to communicate. Along the lines of the yet-to-be-imagined Slack, Discord and the like, it was called Project Burrito, a shared space that allowed everyone to share ideas, comments, access to the latest game builds, and so on. As the company grew, opening their first proper office on 4th and Battery in 2003, Burrito continued to be the main tool by which company communication was conducted. “When there was a new build, we’d post it on Project Burrito,” explains Fiete. “And everyone could see it, they could make comments on it, have different ideas.”

And he means everyone. As the business grew, whether a secretary or web designer, the whole company was involved. It began with the quality assurance team, then spread. “Even in the early days, that was their number two job,” says Fiete. “Number one, find bugs. But you’re going to be expected to contribute feedback to these games. We extended that to everyone as time went on.” It was a system that made perfect sense. As a company designing games for audiences of non-gamers, they found a way to utilize all the non-gamers in the company to keep this focus.

It was a system that meant talent could be spotted anywhere in the business. Joining the company in 2005, Anthony Coleman was employed as a sysadmin, keeping the email running, building computers. “I was the 22nd person in the company,” he tells me. “And it really was a big family. Pretty much all communications were public, and everyone could view everything. There wasn’t a wall between people making and not making games. They wanted feedback. ‘Here’s new builds of our games, play ‘em, tell us what you think.’” At the same time, available to anyone in PopCap was access to the proprietary 2D engine in which they built their games, and Coleman started putting together prototypes in his spare time.

“Eventually I showed them to the studio,” says Coleman “And after a year and a half they said, ‘Yeah, we have a job for you in the studio. We want you to take Bookworm Adventures and make a web game out of it. Go.’ Which was trial by fire, it was a blast!” Coleman went on to be the project lead on Bookworm Adventures 2.

This combination of a willingness to try new business models, alongside the amounts of money Bejeweled was bringing in, afforded PopCap the ability to spend vastly more time making small casual games than anyone else in that industry. Games like 2007’s Peggle, the Bejeweled sequels, and the Bookworm series, were given years to be created. This was into a market where almost everyone else was focused on churn. PopCap’s long-time PR guru, Garth Chouteau, told me how he’d played a build of Peggle nine months ahead of its release and responded, “Well, this is fucking amazing! Why haven’t we put this out yet? Let’s just ship it tomorrow!” But the ethos at the company was to keep holding games back, keep refining, keep adding.

“There wasn’t a pressure that things had to be released at specific times,” explains Anthony Coleman. “Almost all those games took two to three years to make. People thought, that’s so long for these small games. But Bejeweled gave a very long runway for each project. And it meant we could spend a year and a half on a project, think it’s not going to go anywhere, and just can it.”

It also helped that the company made decisions that weren’t exactly… normal. For instance, when they discovered that someone had created a bootlegged version of Bejeweled, using their assets, and then ported it into World Of Warcraft, their response wasn’t lawyers. Their response, Coleman recalls, was “‘How about we just pay you, and you make it good?’ And he did! He came to work for us for a number of years.” Which is how it came to be that WoW featured Bejeweled, and later Peggle, as games to play while on flightpaths.

And this wasn’t a one-off. PopCap was no stranger to controversies over ‘borrowing’ from other games. (On the Zuma/Puzzloop contention Kapalka says, “I can’t deny it, we definitely were inspired by Puzzloop. We thought it was dead, we found it in some MAME archive from 10 years ago, and had no idea it would be missed by anybody if we borrowed some of the mechanics.”) But it went the other way far more often, and their response was almost always to reach out.

Garth Chouteau brought up another extraordinary example. While Bejeweled was ported to almost any device you could think of, one PopCap hadn’t opted for was the original GameBoy. A man called Bernie King decided to make it himself, because his girlfriend was a huge fan. “So he hacked it onto the Game Boy for her and then programmed in a special level to drop a diamond ring from the top and ask her to marry him. When we heard about that story, we thought it was so cool that we helped pay for the wedding. We paid for a Bejeweled cake and Bejeweled-themed decorations for the wedding and reception.”

Or the time they found out someone was producing ceramic Plants Vs Zombies garden decorations, and responded by asking him to make them 900 of them, handing out sets to press for a promotional event.

All this time, PopCap had found its comfort zone. Working hard, for years, to create incredibly approachable games, to sell primarily to a casual gaming audience, via casual gaming portals. And yet despite this, they eventually found their games were being played by the so-called ‘hardcore’ players. Their first realization of this was the day Valve called them up to yell at them about Peggle.

“Before that, it was pretty much moms and grandmas,” says Kapalka. “I think Peggle was the first crossover we had with the hardcore audience.” Their games were being sold on Steam, mostly as an experiment, and had started catching a new audience’s attention.

The call from Valve is remembered by everyone slightly differently. Coleman recalls they said, “We really enjoy Peggle, but we also hate you, because you’ve destroyed productivity for the past 48 hours. No one has done any work, they’re just sitting around challenging each other to get high scores in Peggle.” Chouteau remembers it as their “begging Sukhbir [Sidhu, Peggle’s project lead] to tell them how to beat the last level of Peggle so they could get back to work.” And Vechey says they said, “You’ve single-handedly slipped Left 4 Dead. Everyone’s playing it, there’s an internal competition, and it’s screeched development of Left 4 Dead to a halt.”

In response, PopCap made a goofy version of Peggle featuring Valve icons like headcrabs, and sent it over to them as a gift. Valve replied saying, “Can we put this in the Orange Box?” PopCap said, “What’s that?” This led to PopCap’s creating that special edition of Peggle that appeared in PC versions of the legendary Orange Box, with Half-Life, TF2 and Portal-themed levels. Their journey to the specialist side had begun.

But it was 2009’s Plants vs. Zombies that completed the transition. While Bejeweled was still selling vast numbers in every iteration, on every platform, PvZ was PopCap’s biggest, most expensive project to date. And it wasn’t one they were at all sure about. Firstly, it was a far more complicated core idea, taking tower defense and trying to broaden its appeal to the masses. Secondly, you know, zombies. But with their attitude of trying things out to see where they went, they hired project lead George Fan to set up a new studio in San Francisco, and gave him time and funds to prototype it.

“Working on PvZ was really a golden window that I don’t think many people get to experience,” Fan tells me. “The joy of working on it, everyone having such a great time, reflects on the game itself. The situation making PvZ was really a Goldilocks zone. PopCap let us make what we wanted to, and they trusted us to make the best game we could. It was a pretty small core team, everyone on the team got along, and we were extremely productive together. There were so few hiccups.”

The name “Plants vs. Zombies” was originally a placeholder, and it looked like it might stick until a colleague of Fan’s suggested “Lawn Of The Dead.” Instantly everyone knew that’s what they wanted it to be called. So much so that Fan reshaped the entire game to match it. “In the final version you play on your front lawn,” says Fan, “but prior to that it had been set in a back garden dirt patch.” Yes, that’s why it’s a game in which you strangely plant flora in your lawn—for the pun. And then they checked with the lawyers. Because of George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, of course.

Inspired by, of all things, a School Of Rock DVD extra in which Jack Black appealed to Led Zepplin to let them use their songs, Fan put together a video of himself dressed as a zombie programmer, growling at the camera. The subtitles read, “George Romero, please let us grace this game with your beautiful name.” They sent it off to Romero’s production company, excited to hear back. Fan continues, “I don’t think they saw it. We just got a form letter back.”

Heartbreak. In the end, despite similarly unlikely suggestions like “Residential Evil”, they went back to Plants vs. Zombies, but not without later getting some sweet revenge.

Seemingly entirely unironically, a few years later Romero’s production company got in touch with PopCap. Fan remembers it with relish. “‘Hey, we have a great idea. Would you like to cross promote PvZ with one of our new movies coming out?’ I didn’t get to write the response, but I heard it was very satisfying to write. Like, ‘Hell no.’”

In fact, the person who did get to write the response was Garth Chouteau. “I was the revenge moment,” he tells me. Disparagingly remembering Romero’s appeal he says, “It was just this sort of overture, ‘Can we somehow leverage your super-hot brand for our horrible fifth follow-up sequel movie?’. [I replied] ‘You know, you shot us down three or four years ago when we begged to be able to use Lawn of the Dead, so I don’t think so. I’ll run it up the chain, but I don’t think so.’ It was very satisfying. I remember circulating that email going, hee hee, who’s the hot property now, boys?”

Plants vs. Zombies didn’t sell at all well in PopCap’s traditional spaces. “But where it did well was on Steam,” says founder Jason Kapalka. “We knew the guys at Valve and got on well, but even having a casual game like PvZ on Steam was a bit of an exception.” And it seems this was the moment where things could have gone in two very different directions for PopCap.

PvZ found an audience on Steam, but it found an even bigger one once it was ported to the burgeoning iPad and iPhone market. And then all of a sudden, Facebook happened.

In every conversation I had speaking to former PopCap employees and founders, a sadness came to their voice when it came to talking about Facebook. The consensus seems to be that this was the first time they tripped up, the first time they didn’t understand a market. “Who’s going to pay money for cows?!” cried Kapalka, a sudden switch from his soothing Canadian drawl when the topic came up. He was referring to FarmVille, of course, the game from rival casual game studio Zynga that defined gaming success on the social network. As a company that had been at the forefront of multiple online gaming trends, not getting a good read of where things were heading on Facebook caused consternation. Some for not recognizing a new market, others because it just wasn’t a direction in which they wanted to take their games. “I kind of wish we’d just ignored the Facebook era,” says co-founder Brian Fiete, real regret in his tone.

It even affected the near-manic enthusiasm of PR man Garth Chouteau. Remembering a new Peggle that was designed for Facebook (“Oh man, that was going to be so fucking cool,”), his voice shifts and he adds, “I don’t know why it didn’t make it to market, but we did not do well on Facebook.”

It was around this time, early 2011, PopCap created an alternative label, Fourth & Battery, to release smaller, more obscure, less family friendly titles. Game jam ideas that weren’t quite hooky enough to become full-fledged projects. Or, as I would suggest, a company getting itchy feet and not really knowing what to do with itself.

From my conversations, it seems morale became a significant problem at PopCap. “The way we were making games was different,” says Fiete. “It became half game design, but half marketing, A/B testing. The whole Facebook movement was pretty damaging. This concept that you make a game, and you can just throw crap in it, then you do an A/B test. And if that crap works you leave it in, and if it doesn’t work you take it out. This is how some of these managers would see game design. This was something we never had to fight before.”

It seemed a sale was inevitable. In fact, they’d come close on a few occasions before, different people’s recollections suggesting between five and 11 times. Coleman, who was not in the upper management, recalls the atmosphere in the months leading up to 2011’s sale to EA. “There was a fair amount of uncertainty in the company at that time. We’d grown a lot. There were like 600 people in a ton of offices. There was a lot of shift in what our focus was going to be. Should it be on PC? Should it be on Facebook? Should it be on iOS? There were a lot of games that didn’t see the light of day at that time. It was probably seven months before EA buying us in 2011 there was a clear idea that something was changing. Something big was going to happen.”

On July 12th, it was announced that EA were buying PopCap for $650 million plus stock options. During my conversations with former PopCap staff, I’ve heard numbers as high as $1.2bn were on the table if further targets were met. No one’s going to say no to that offer. (Although Vechey notes, “I think that someone can make that much money off the labor of others... that that’s an option, is something that’s wrong with our world. Yeah, who can say no to that? But why are we letting people make choices like that? How can we justify that level of wealth creation and the level of inequality and suffering we have in the world?”) Of course, the received opinion is that EA then immediately set about turning PopCap into a microtransaction machine, squeezing their customers for every last cent, until all the magic was wrung dry from the company. But no one I spoke to saw it that way. Because, mostly, they acknowledged PopCap was already heading in that direction on its own.

Fiete is the most blatant about it. “We put ourselves on that trajectory maybe a year and a half before we sold to EA,” he tells me. “The sale to EA was because that trajectory was so successful—at least momentarily—and we had these huge revenue projections. Some companies like EA were willing to pay money based on those Facebook revenue projections, and it was just too good to say no to.”

“We weren’t sure it was the right thing to do,” says co-founder Kapalka, “but there was a sense that we’d doubled down on the roulette table quite a few times, and weren’t sure if we’d keep getting lucky in the future.” He later adds, “There was always a battle at PopCap, once all those microtransactions became very common, initially on Facebook games, and then mobile. There was a lot of internal dissent about that.”

After the sale, all the people I spoke to gradually moved on. Some stayed for months, some a couple of years, but all found it just wasn’t a place they wanted to be anymore. Anthony Coleman put it neatly. “We were less and less interested in making what we were told we had to make at that point, which was mobile free-to-play. Then there were more restrictions, because it needed to be the biggest audience possible. And we had other ideas for games we wanted to try, and we knew we’d never be able to make them here. It was time to just move on.”

What alternate timeline could there have been for PopCap, had the sale not happened? While many acknowledged it was very possible the company would be in a similar place, working on free-to-play mobile games simply because that’s where the casual market is now, there were also wistful thoughts about never having backed down from that $20 downloadable format.

Fiete is the most optimistic. “I [wish we’d] kept making downloadable games that went on sites like Steam. That would have been a different route for PopCap, and we probably wouldn’t have ended up with as much money, but I think we’d still be making those PvZ type games right now probably.”

Kapalka is more hesitant. “It’s hard to say. Maybe we’d have done well and be a huge company now, or it’s possible we’d have crashed and burned.” While Coleman offers a left-field observation. “We almost bought Runic right after they released Torchlight. We had a studio get-together. It in the end fell through. I think if we’d acquired Runic the trajectory for PopCap could have been very different.”

And it’s worth noting that John Vechey, perhaps the most open about his regrets, remains enormously proud of the PopCap that does exist. “I went down to the new PopCap offices last year. I’d prepared some words, but I wasn’t ready for the emotionally overwhelming experience of entering this office. It was not PopCap, but it was not not PopCap. It was also EA but not EA. There were people there who, when we hired them, were super-new to their careers, and were now leading these things. They wouldn’t have been able to do that if PopCap had stayed PopCap. They were pushing on what made a PopCap game a PopCap game. And I was really proud of that. It still had the DNA and legacy of things we had done. That was really neat.”

Despite the despondency about how things came to an end, everyone recalled those days in the 2000s with incredible fondness. This close team, working in an open fashion, where any idea was allowed time and cash to see if it could fly. “I feel like I got my education in game design there,” says Anthony Coleman. “This is how you pay attention to details and critically think about how people are going to interact with parts of the game.”

“The three and a half years on PvZ I will cherish forever,” George Fan says, real brightness in his voice (he’s a man the designer Edmund McMillen once described as “very E for Everyone”). “That’s as smooth and as great as making a game is going to get.”

“My favorite time was when I knew everyone, I knew everything that was going on,” suggests Brian Fiete. “Board meetings were very boring because I already knew everything that was going to be discussed. 2004, maybe 2005—that was the sweet spot.”

“We probably built a business around creativity better than many have been able to,” says John Vechey. “We were never purists, but nor were we just trying to make a buck. We had these consultants come in, and we paid them too much money—at the time it seemed an incredible waste of money, in retrospect it was a drop in the bucket—and they came in and said, ‘What’s your vision statement for PopCap?’ Jason says, ‘Make great games?’ They’re like, ‘THAT CAN’T BE ONE!’ But in retrospect that’s exactly what it was.”

Note: We approached the elusive Sukhbir Sidhu for this article, the creative force behind Peggle, but unfortunately got no reply.

John Walker has been writing about video games for over 20 years, and was one of the founders of Rock Paper Shotgun. He’s currently running buried-treasure.org, highlighting excellent indie games that don’t get covered elsewhere.