Premature Evaluation: Timeflow

For sale: happiness, never worn

Hello again, it’s me, the premature evaluator. When I’m not prematurely evaluating things, you will often find me sabotaging my own life through chronic mismanagement of my bank balance and available free time. For example, I am writing this article in the very last moments before it’s due to be published, not because I have an especially pressing schedule – I’ve spent the last five hours preparing to write by eating cold leftover curry, having a big nap on the sofa and watching old episodes of Pointless on iPlayer – but simply because my brain refuses to operate without a hard deadline looming on my mental horizon, like a bad Godzilla.

So yes, I am terrible at doing things on time, but at least I’m also awful with my money. I spend everything I earn on rent, trains and Quorn scotch eggs. I bought a bitcoin at exactly the worst possible time you could do that. Rather than saving for my retirement, I plan to walk backwards into the ocean on my 65th birthday, smiling at my grieving children as they wave spotted handkerchiefs from the beach and noisily weep. The closest thing I’ve got to a pension is the misguided but firmly held belief that I will one day stumble across a treasure chest filled with emerald tiaras, and then everything will be fine. Or that Mecha Fiona Bruce will value my collection of Pokemon trading cards at ten million pounds on Antiques Roadshow 2050, and then everything will be fine. I am nothing if not an optimist, albeit one perpetually on the brink of ruin.

Which brings us to this week’s premature evaluation. It’s called Timeflow, and it’s a board game (a horror game, really) about properly managing your time and money. It’s basically the Game of Life, except rather than driving into a heteronormative sunset in a tiny plastic Volvo, you skirt along the cusp of bankruptcy in pursuit of some grand (and very expensive) life goal. You can enter cryogenic stasis, buy a ticket aboard a space flight, own a private island, reject consumerism to live an ascetic lifestyle in southeast Asia (which somehow costs two million dollars), and lots of other things that tedious people claim to aspire to do in later life, when what anyone really wants is to eat too many chips and die alone in front of the television.

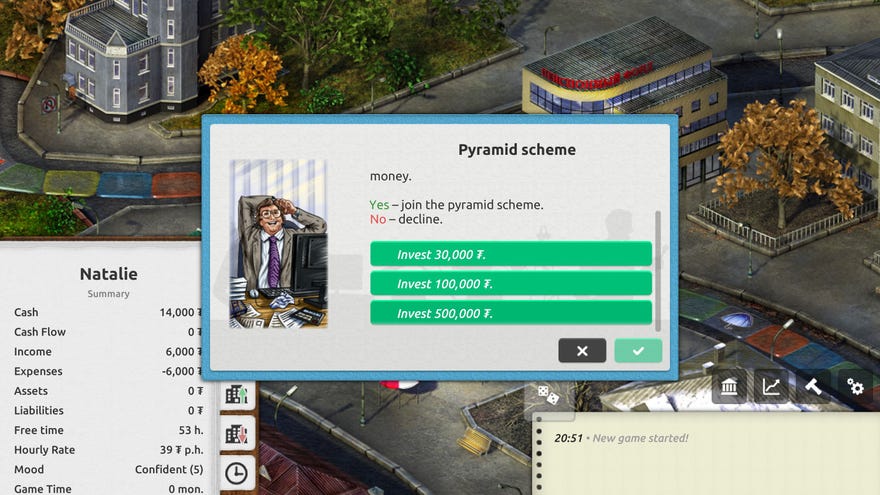

You choose to play as one of a set of characters from different financial backgrounds, each offering a varying degree of challenge. Natalie’s got a crap job, a compulsive shopping habit and no savings, but 53 whole hours to play with. Eugene has put a bit of cash away, but his young kid (and his video game addiction) eats up a lot of his spare time. Children are only ever a liability in Timeflow, the game where all that matters is relentless self-improvement at the expense of all other worldly pursuits. Emotions and love are flashing red deficits in the big balance sheet of life, instead one must hone oneself into a hyper-efficient capitalist torpedo, by investing in real estate, and spending all of your spare time in marketing workshops and hoovering up business degrees to earn bigger and bigger salaries.

Monopoly was invented by board game designer Elizabeth Magie in 1903, to illustrate and satirise the economic shortcomings of rampant and unregulated capitalism. The game’s underlying meaning – now lost on everyone who hasn’t listened to the podcast where I first heard about it – is that economic value derived from land should belong to all members of society. The intention was that, as soon as every player was bankrupt and the system was revealed to unfairly favour one monopolistic landowner, they would immediately leap from their chairs singing The Internationale, and go full-blown socialist.

Today it’s just a bad game about who can own the most tiny houses, but while Monopoly is widely misinterpreted by players, Timeflow seems to be a sincere celebration of the very worst bits of capitalism. It frames higher education as “training”, and degrees as a purely wealth-creating commodity to be pocketed, rather than an academic pursuit with societal worth outside of a fatter pay cheque. You can’t get an arts degree in Timeflow, for example. Why would you? What value is there in knowing about paintings, besides getting the occasional question right on University Challenge?

Instead it’s best to view Timeflow as a scathing satire of the worst excesses of capitalism, rather than a long, cold gaze into the screaming economic abyss of free enterprise. Each roll of the dice moves you along the linear, looping game board, and depending on where you land you’re given opportunities to invest your money in a business, real estate or stocks, or to allocate some of your free time to learning how to more efficiently run a company, or on therapy to treat whatever vice your character is lumbered with. Different events will randomly crop up too. An uncle might try and sucker you into a pyramid scheme, or you might involuntarily spend £800 on some frivolous purchase, like a single, diamond-encrusted brogue. You drag and drop assets and liabilities into your budget as you accrue them, with the goal of maintaining a positive cash flow and a healthy wallet. It’s precisely the sort of fantastic escapism we’re all after.

You can play against any human you can convince to sit down next to you, or against bots, who rather depressingly just vanish into thin air once they’ve run out of money, their little AI brains choosing to simply cease existing rather than suffer the indignity of being broke.

Is it any fun? Not for anyone who doesn’t enjoy an unflinchingly bland simulation of the absolute least enjoyable thing about being alive. Whether it’s the game’s intention or not, Timeflow forces you to reckon with your own miserable budget, like staring at yourself in the mirror during a haircut, as your features become weird and unrecognisable, shifting until you are a stranger to yourself, and then, once the person looking back at you is thoroughly unfamiliar, realising that they are ugly, your haircut is too expensive, your copy deadline is in an hour, and you should probably stop buying so many Quorn scotch eggs.